Process of Illumination

Acadia Currah

So it starts like this. Your mother, she grew up in Newfoundland where Catholic means something else, it means not Protestant, it means proverbs and pews and cardboard bread that melts on your tongue. So when she picks the school, she probably doesn’t think much of it, only that it’s better than the school you go to, that you don’t like it there. She is thinking about your happiness, sometimes it seems that’s all she does.

So you go. And it isn’t so bad. All white dresses and crossed ankles under desks. And more than that, it’s the idea of belonging to something, to someone. So there’s no problem until there is; they need it to be a building. Maybe not a fancy one, but a nice building. And to you, it isn’t. Church is the smell of the sidewalk after it rains, like mud and fresh air. It’s the dandelions in your backyard. It’s the dollar store valentines in your backpack. They take the church out of you in their attempts to put it in. The stuffy air of a makeshift confession booth in the library doesn’t feel like church, or home, or safety, it just feels like a room. And the rain just smells like water. And the dandelions are just weeds, and the valentines are just cheap. And you don’t think about god. Not in the way they want you to.

You think about God and throw salt over your shoulder. You think about God when you’re afraid, or ashamed, or when you take the bread before you’ve had your first communion. You think about God and you feel like you’re going to fall through a trapdoor into a room where they keep the girls they’re ashamed of. You’re the thin mixture of too good and not good enough a Christian.

So you do the “Forgive me father for I have sinneds,” take Hail Marys like multivitamins, be prescribed Our Fathers, sons, and holy spirits like you have any of those. When you pray it sounds like a monologue but any spoken mantra hits your ears like a prayer. Sports games, Wiccan spells, they all sound the same, a repetitive plea to an uncaring man in a throne, or a white chair, or a castle, always a man, always something golden and unattainable. Something opulent and insidious. But you are good, and quiet, and you sit up straight on wooden pews and you pretend you believe, you want to believe. You are the picture of meticulously maintained composure and girls exactly where they are supposed to be. You ignore your hands when you bless yourself backwards out of something like rebellion, call it a lack of sleep, call it a trick of the light. Call it something, anything else.

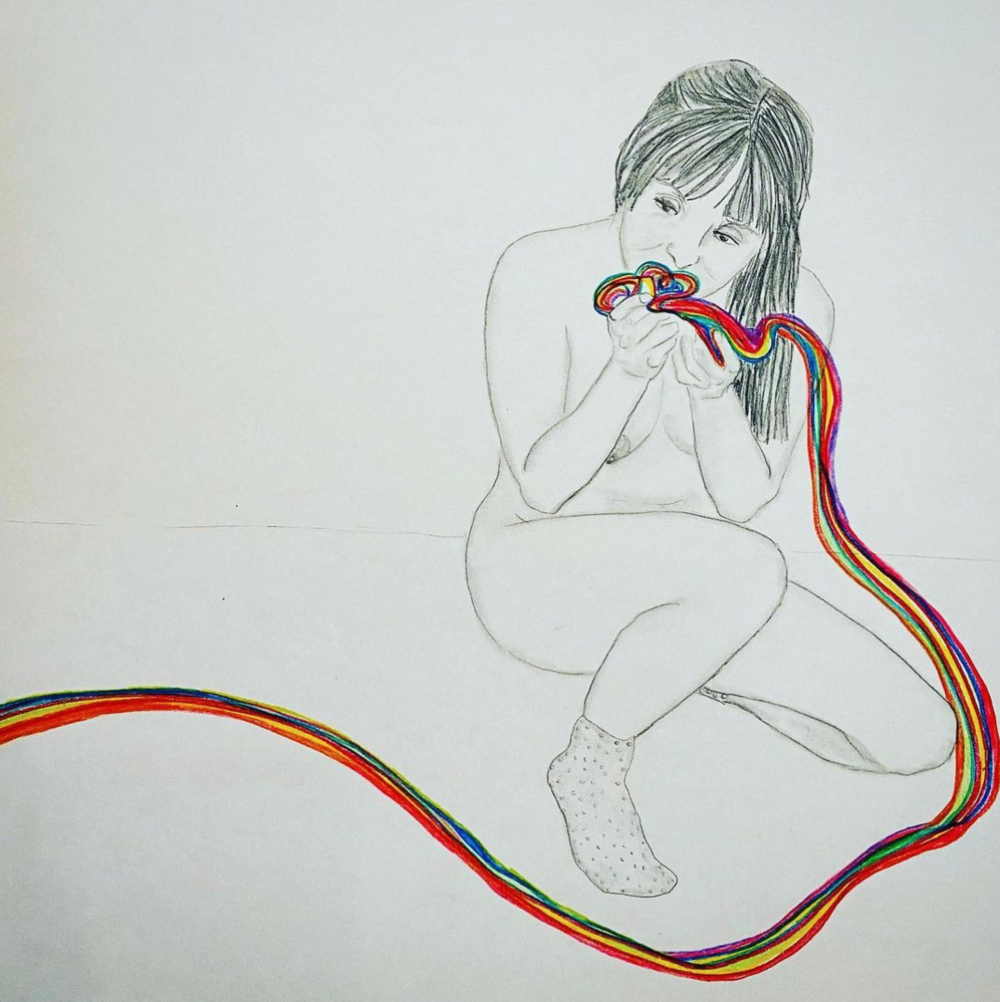

You spend years pressing yourself into cookie cutter Christian girlhood, rigidly removing any parts that do not fit. You feel your body adapt like some other evolution, kneeling instead of standing, head bowed in some semblance of respect, hands pressed together in prayer until they fuse, until it just looks like begging. Until you cannot remember how to stand without apology.

It is brittle, and artificial, so naturally, it breaks. You turn thirteen, and fourteen, and they hate you because you’re not a little girl anymore, because you’re shaped like sin. Good Christian girls stay little, you didn’t know that. You learn. You wear jeans three sizes too small in hopes they will make your legs stay the same size. You treat your body like clay but it hardens into stone, unruly, out of your control. You remain vigilant. “I believe in this.” “I will keep believing this.” “Amen.”

They don’t let you. You wear the same things as before, as other girls, and get written up, your name on a list that might as well be labeled “The devil’s associates,” might as well dictate your descent into hell. You were wearing something long-sleeved that hit the hem of your jeans but it doesn’t matter. “Coke bottle,” “Hourglass,” and you wonder if they will ever stop comparing you to objects. “Distracting the male teachers,” “Do you have something in your locker you could change into?” “Identify the passage in the bible in which Jesus places value on modesty.” You are no longer fluent in the language of faith. Your prayers fall flat, unconvincing, how could they be effective when the person delivering them looks like the very thing they are condemning? You look like an unholy desire and the feeling burns a hole in your chest shaped like the rosary beads you used to wear.

The girls in your class talk about body types going in and out of style, the inherent sexism of needing to look a certain way, needing to achieve a certain silhouette. Your lunch rots in your locker and they don’t let their boyfriends talk to you. “Guys don’t want to date girls that look like you.” And you are too young to understand why one of them lingers over the word date like there’s some double meaning. Some hidden thing that, freed from the constraints of a school hallway lined with crosses, she might say instead. There is.

They say “Catholic guilt,” and you call it that too. The gnawing, raw, unrelenting feeling that you are letting someone down. That your existence is an inconvenience to some cosmic superpower, watching your worst moments replayed on some giant screen otherwise seen at sports games, the kind you always hated attending. It feels distinctly un-Catholic, so removed from the ideal of polished bronze crucifixes and stained glass portraits of beautiful people that it feels almost sacrilegious. God condemns liars and sinners and people who eat pancakes for breakfast and nothing for dinner. The gluttonous and the vain. You fall into some sick purgatory between the two, able to chew your food but unable to swallow it.

They want you to suspend your disbelief and kneel at an invisible altar, offering your prayers and free will as penance for sins you’ve committed, dictated by a book you haven’t read. They turn you from it, they tell you you are a bad Christian so you become one. You cross your fingers behind your back when you swear to God and drink communion wine after the sermon is long over. You do not think about God when you step over the threshold of a church, hair on your arms standing on end and static in the air. Your chapel tights have runs in them and your mouth spits the words of hymns like the guitar heavy bridge of a rock song. You do not think about God, but you think about creation.

You are volatile, and you want to punch a hole in the sky. You want to open heaven and shake out its inhabitants, ask them who you have to slip twenty dollars to under the table. Ask them how they lived free of sin while still being human. And God isn’t your father in heaven, he’s the referee at your soccer game, and the critic in your audience, and the college admissions officer stamping an inky bright-red ‘Denied’ on your application. God is not the jury but God is the executioner sharpening his sword in slow, sickening strokes like he thinks you’re listening. You are.

You join the legions of teenagers staring at the wall during sermons wishing they were anywhere else, feeling guilty for wishing they were anywhere else, wishing it more. They put ash on your forehead and you know what all of the advent candles mean. You wonder if wanting to believe is a substitute for sincerity. It isn't. You learn that people are like chameleons. Your dad learns to sleep into the day and work into the night. Your mom must need blue light glasses to spend eight hours a day at her computer. You wonder why when they dunk you under holy water you do not grow gills. You wonder why you cannot breathe.

Everything makes you feel ashamed. You apologize for apologizing. You cannot drink something hot without it sitting in the pit of your stomach, the distinct fear that you are enjoying it too much is ever-present, heavy like lead. You learn to identify this “Hand in the cookie jar” feeling more, learn to fear it, let it coach you out of eating cupcakes, going roller skating, naps, telling jokes, writing poems, laughing, seeing your friends and wearing earbuds under your braids at church. You are a girl and you are a student and you are young but you are not alive. There is no breath without consequence, there is no joy free of sin. You feel like you’re in some horror movie trap with a wall of spikes closing in on you from all sides. Like you’re some helpless side character who is only allowed to cry if she looks pretty while she does it.

And for something built around the idea that light is all that is good, it is hard to find a pocket of natural light in a church, all candles or distorted colours. Darkness is only juxtaposed with the idea of light, and this idea should be enough. That blind faith is the only way, the only true way, to believe. You believe in the bird’s nest outside your window, in the sun warming your face in April after it’s been snowing for six months, in the creases in your sneakers, in the snort of your best friend's laugh. You believe in things infinitely bigger and smaller than God. You are not allowed to say this yet. And once they’ve fed you your proverbs and your testaments and your psalms you wonder when they will let you put down your cross.

Acadia Currah is an essayist and poet residing in Vancouver, British Columbia. She writes, primarily, about gender, sexuality and religion, especially as it pertains to being a young queer woman in Canada. She is in her first year at the University of British Columbia and this is is her first published work.